Stories

Intermediaries and Witnesses

For years, Stephansplatz in Hamburg has been home to a stand-off between the Warrior’s Monument from 1936 and a counter-memorial installed after the war. The recently installed Deserter’s Monument creates a bridge between the two pieces and tells of the struggle of injustice in German history.

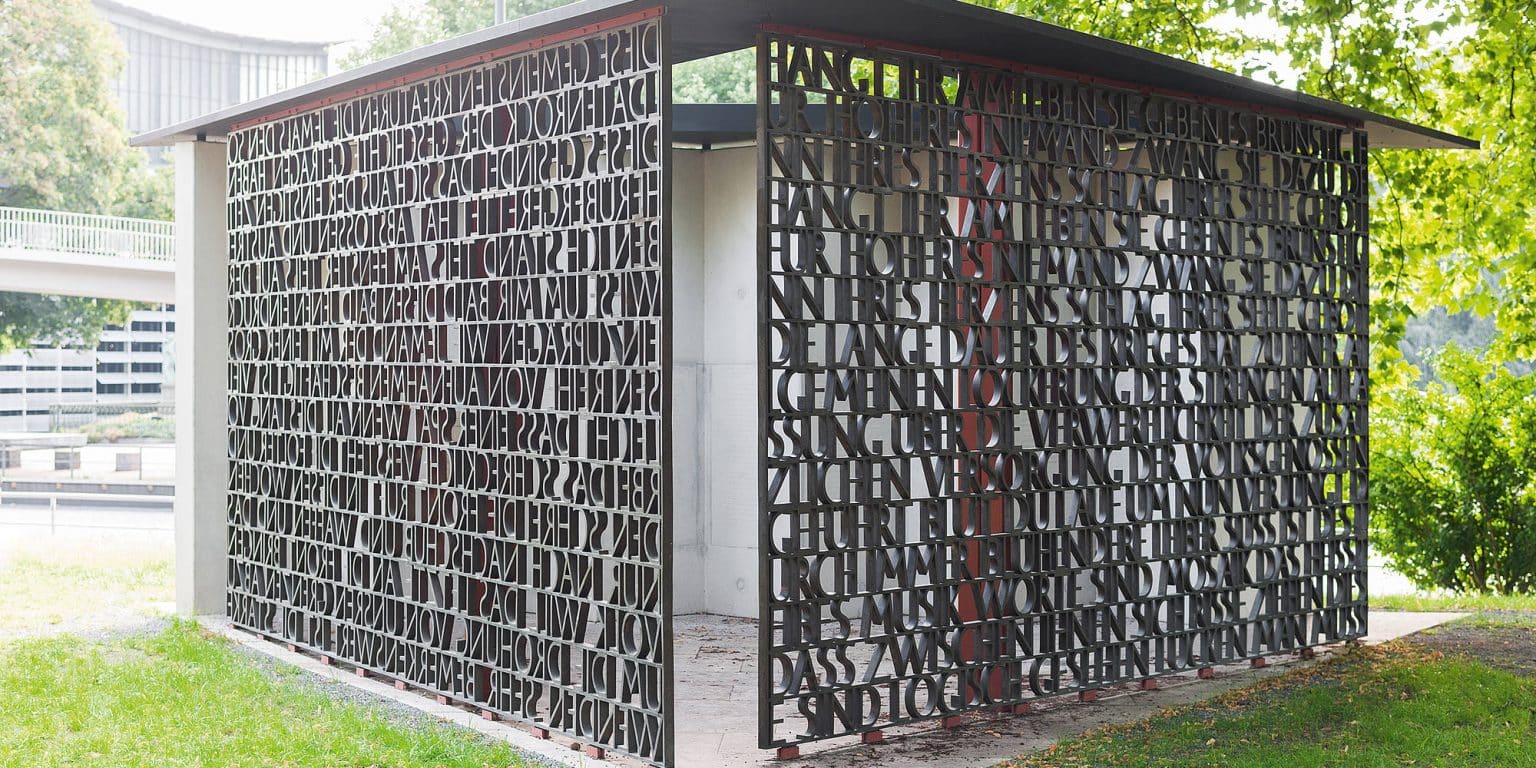

It’s a grey and windy day in March 2016 as Volker Land stands in front of his installation. The memorial he designed for Stephansplatz in Hamburg honors the victims of National Socialist military justice in Hamburg. “Desertion is a form of resistance, not just about the fate of an individual,” said Lang. This is the thought behind the memorial, conceptualized as an accessible equilateral triangle: with a concrete wall engraved with historical information, a sound installation to 227 victims, and two bronze grids of letters with excerpts from the collection of quotes ‘Deutschland 1944’ by Helmut Heißenbüttel. “The word ‘deserter’ is often used as an insult. It’s about the values that come with deserting,” said Lang. He means: human, ethical values. A topic relevant for our times.

Lang’s work, revealed in November 2015, stands between the Warrior’s Monument by Richard Kuöhl from 1936 and Alfred Hrdlicka’s counter-memorial from the eighties. The new work was intended to create a bridge between the two different times and perspectives.

Designed off the back of Nazi values, the Kuöhl monument honors Hamburg soldiers in the First World War with an inscription meaning “Germany must live, even if we must die”. After the war, the British occupation authorities wanted to demolish the monument but the Hamburg Conservation Council intervened with an offer to remove the controversial relief and inscription. This project was never carried out – but the people of Hamburg’s rejection of the monument even became part of their language – the monument is referred to locally as the ‘Kriegsklotz’, meaning ‘war stump’.

Later discussions on desertion

In the 80s, another monument was planned to calm the situation. The Austrian artist Alfred Hrdlicka designed the ‘Warning Against War’. Its four parts represent the bombing of Hamburg, the deaths of concentration camp prisoners in the sinking of the Cap Arcona, deaths of soldiers and the image of women under fascism. The project was halted in 1986 due to budget issues. Only two of the four parts were finished.

More than two decades later, there was a third attempt: the two monuments were to be joined by a third. The fact that it took two years until the project was opened for competition in 2014 shows just how hard it still is today to recover the struggle of victims of National Socialist military justice.

Judgements made by the military courts against deserters from the Wehrmacht army were only overruled in 2002. Dr Detlef Garbe explains that discussions about these deserters only begin in the eighties. The director of the concentration camp memorial in Hamburg-Neuengamme was entrusted by the Ministry of Culture with carrying out research for the monument. Garbe states that it took 40 years after the war for people to realize that military justice was affected by National Socialism and no longer upheld the law. As the war generation finally left the public eye in the mid-nineties, there was a new openness about dealing with the topic. Clearing up matters from National Socialist times became less and less moral and emotional – allowing a new assessment and evaluation of the injustice of military justice. Freiburg historian Professor Dr Wolfram Wette recently made the point in a speech “that ‘communicative consciousness’ was changing into a ‘cultural consciousness’.”

Walls of bronze letters

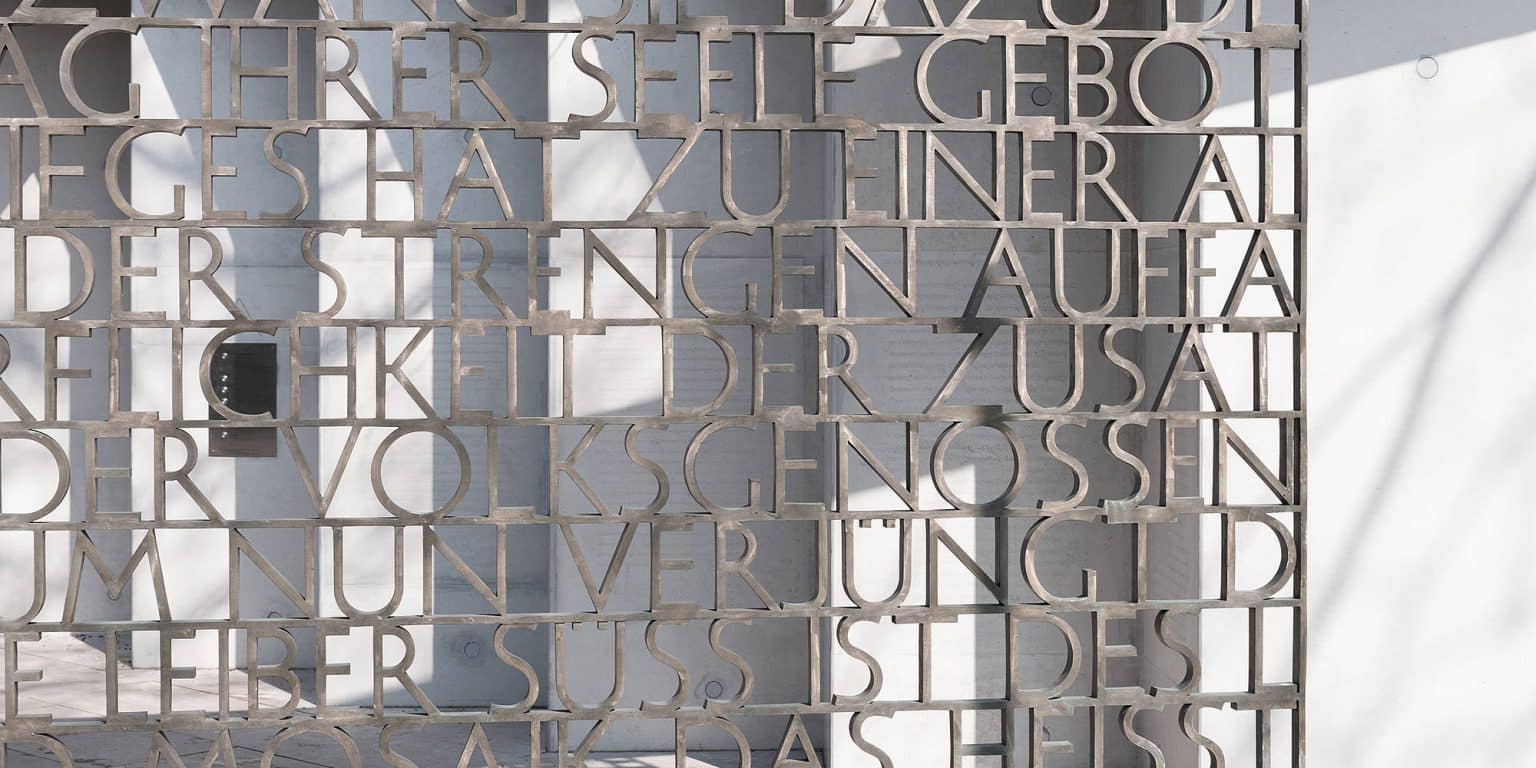

Lang’s memorial shows this change: if Hrdlicka’s design is accusatory and full of warning, Lang’s triangular building is easily accessible – both literally and figuratively. The three walls surround an accessible room, designed to be a meeting place. Two of the walls create a floating text made of bronze letters – excerpts from Heißenbüttel’s unsettling poem ‘Deutschland 1944’. The walls of letters are light and allow you to look inside or outside, depending on your location. They connect the memorial site to its surroundings: the text allows peeks of both the anti-war memorial and the warrior monument, of yesterday and before.

The bronze walls may seem light and airy, but their two tonne weight presses down on the U2 Ubahn line underneath. The folded concrete wall at the back closes the room to the east and protects it from the noise of the four-lane Dammtordamm road. On the inside, there is a sound installation in honor of 227 victims of Hamburg military justice. You can also hear the fragments of poem personally read by Heißenbüttel and built into the memorial.

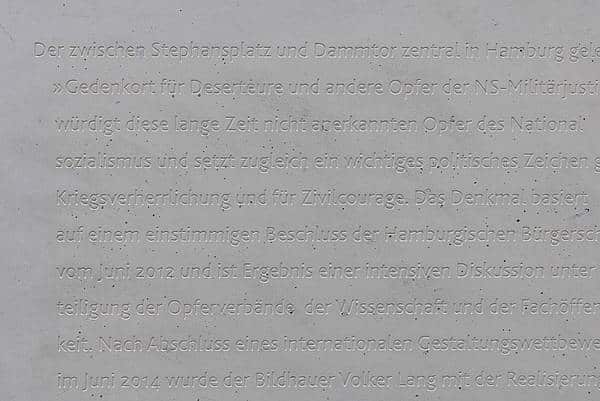

Inscriptions in the folded concrete wall explain the memorial and its context. This was created by RECKLI. “The challenge was to place the inscription into the concrete and guarantee its readability,” said Stefan Besteher, Area Manager at RECKLI. The inscriptions were modeled and transformed by computer into a file for the CNC machine to be milled into board material. “We had to use a V-formation for the letters in the folded wall. Otherwise, there would have been air bubbles in the exposed concrete, which would result in holes that would impair readability,” explained Besteher. The finished formliner was transported to Hamburg and was used for in-situ concreting at the memorial site.

Changing monuments

RECKLI is also implementing the design of the eight columns to be placed at different locations in Hamburg, referencing the memorial itself. They are being manufactured using the artico process. “It makes it possible to show text and images in different shades of grey on the concrete board,” explained Besteher. This process uses films with concrete admixtures that delay the concrete’s setting. A final washing process creates light and dark effects on the surface that allow the text and images to emerge.

The finished monument is already changing: “The inscriptions on the folded wall are really clear at the moment. We’ll see how the indentations change color over time due to the weather.” For the artist, this development of the monument is welcome, as it will grow into its environment – a new stage of meaning in the course of the memorial.