Stories

Building a great neighborhood

Apartments are urgently needed in cities around the world. However, the quick creation of new living space does not have to result in the prefabricated architecture commonly used in the former GDR. In Berlin, Heide & von Beckerath have created a building that reconciles cost-efficient construction with GDR design. In Switzerland, the architect Heinrich Degelo takes a back seat when it comes to interior design, giving the residents completely free rein. In bustling Seoul, Archihood WXY architects create valuable privacy for residents through the innovative placement of balconies.

Architects in Berlin, Basel and Seoul show what urban living will look like in the future: ecological, communal and affordable.

Only few tourists get lost in the Fennpfuhl quarter in the Berlin district of Lichtenberg, although the area is very interesting. For it was here that people worked on the future of housing in the GDR of the early seventies. In its housing construction program, the GDR government attempted to fight the housing shortage with the help of industrial production methods and developed the now much-maligned precast slab housing.

In this environment – pure slab buildings – the Berlin architectural office Heide & von Beckerath realized a residential building on behalf of the municipal Berlin housing association HOWOGE. The starting point wasn’t all too different in the GDR: Living space has become rather tight in Berlin. Since 2008, rents have increased by 350 percent. It has even become difficult for the middle classes to find an apartment.

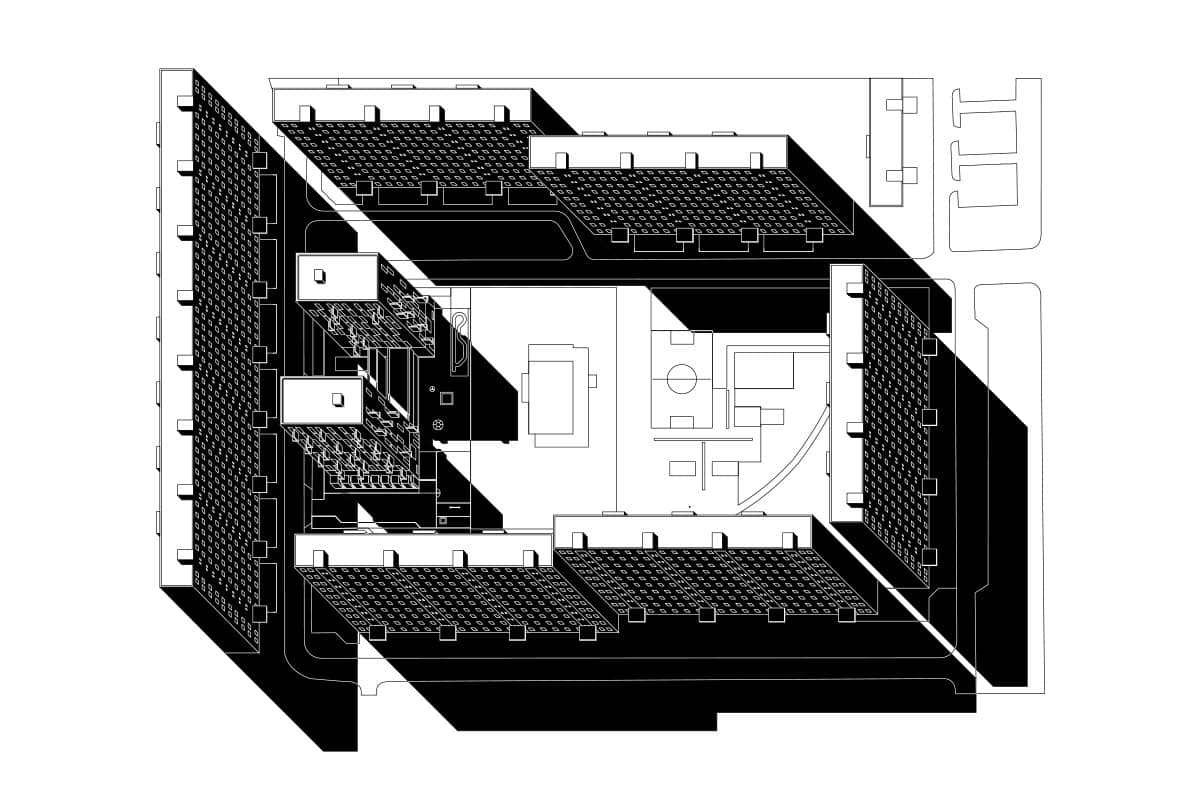

Housing project, Paul-Zobel-Straße

Architect: Heide & von Beckerath

City: Berlin, Germany

GFA: 7,922 sqm

Year: 2017 – 2019

New living space is urgently needed in the world’s urban centers.

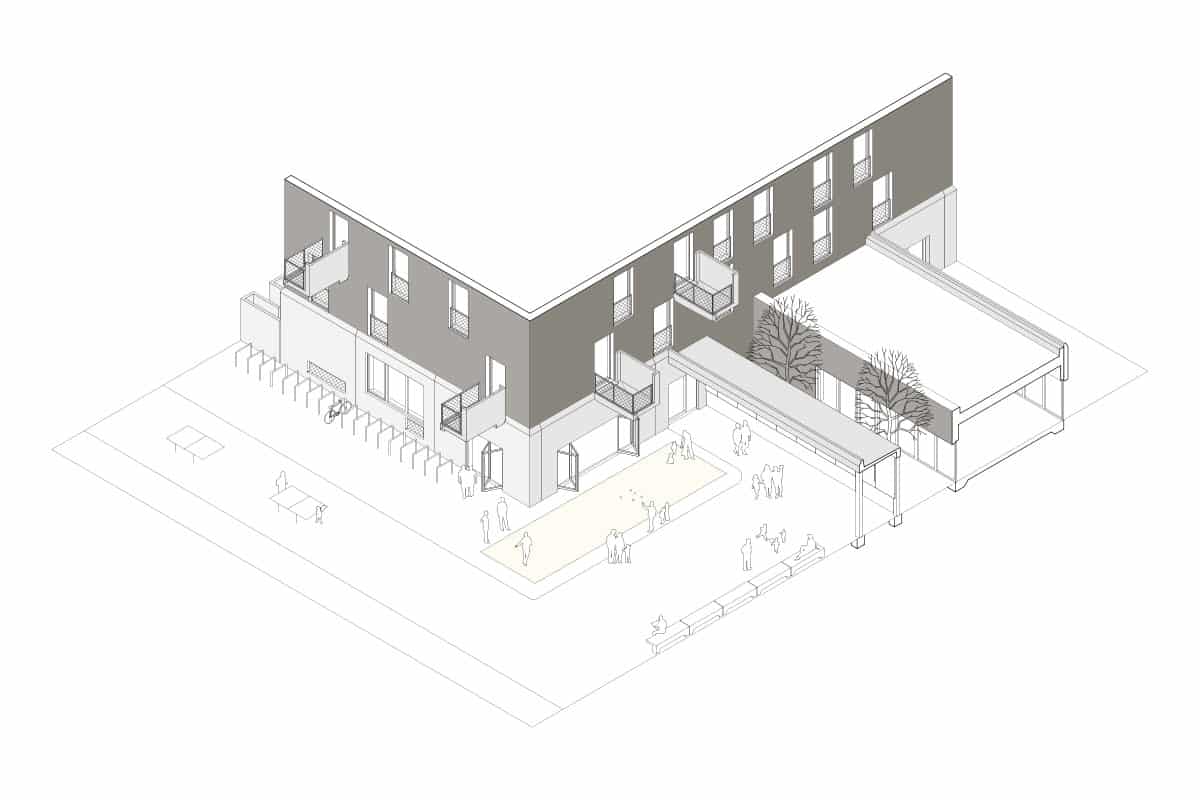

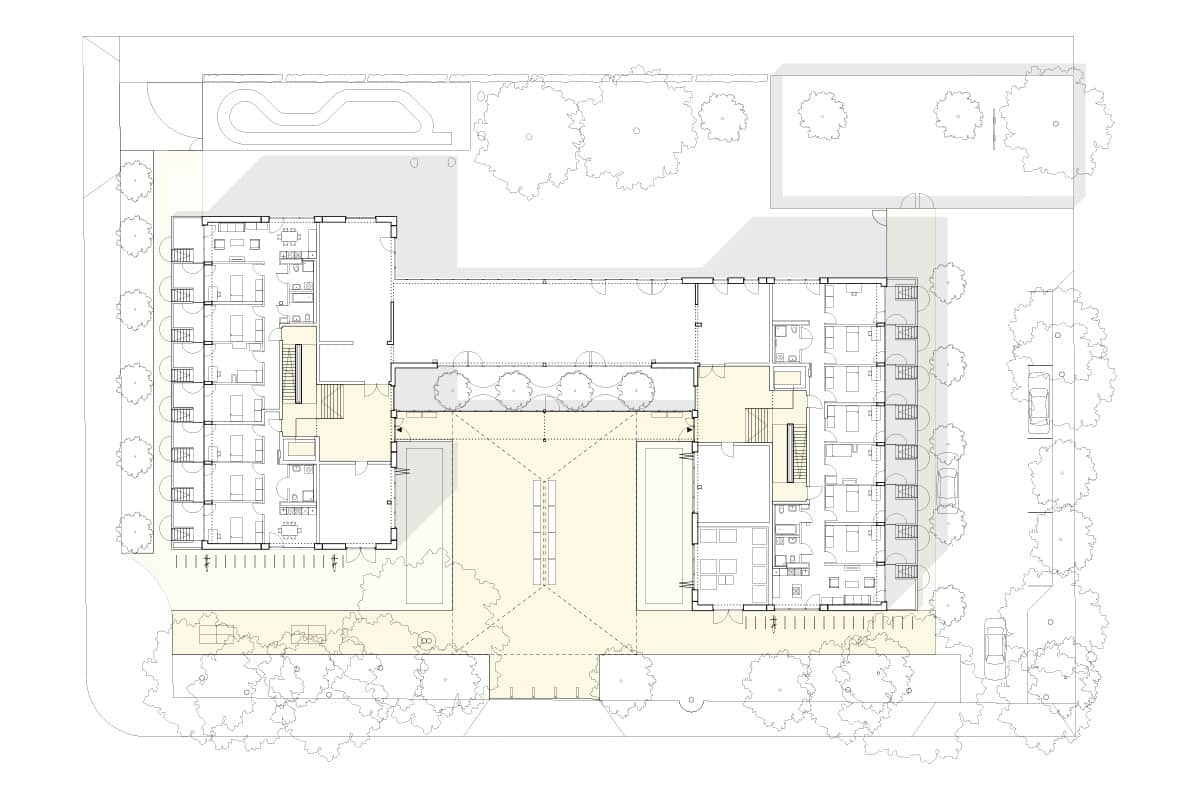

But the recipes of modernity with their uniform standards no longer do justice to today’s societies with their diverse lifestyles. Ecological requirements have also changed considerably. Heide & von Beckerath therefore faced the challenge of building cost-effectively while avoiding the mistakes of the slab buildings. The outcome is two eight-story residential towers on 4,000 square meters connected by a flat base. Of 69 new apartments in total, a third have social subsidies with rent starting at EUR 6.50 per square meter.

Elements from slab construction reinterpreted

Façade and balconies, housing project, Paul-Zobel-Straße, Berlin ©Andrew Alberts

For the Berlin architects, lowering costs means to simplify construction without giving up the architecture. “There are only very few elements in this project,” explains architect Tim Heide. “We are trying to recombine these in the sense of an innovative architectural concept in cooperation with the state-owned housing association.” The windows and balconies have identical formats in the Berlin apartments. Their varying distribution across the façade and the balconies projecting by an unusual 2.70 meters breaks the serial monotony of the conventional slab building. Precast concrete elements are used for the balustrades of the balconies and the canopy of the base building. Heide & von Beckerath combine this link to the GDR building culture with highly insulating, expanded concrete blocks for the exterior walls and thus do without a thermal insulation composite system.

The architects combine modern ecological requirements with those of an economical building method, as it was practiced in the GDR.

The planners solve the problem of the first floor through a lively range of uses. The small apartments created there have an own entrance and a small outdoor terrace, making them more appealing. A German-Russian day care center has also moved in. Instead of an underground garage there are bicycle rooms with sliding doors connecting to the courtyard. The residents can clear out the unusually large areas and celebrate parties together. There are 2 – 5 room apartments on the standard floors. They all have the same core area, which is the transition between rooms. “The transition area can optionally be closed with a door. Without a door, the apartment becomes a loft with an open-floor design,” explains Heide. A minimal, nearly cost-neutral intervention fundamentally changes the apartment’s character and enables flexible uses.

Freedom of design for the residents

Architect Heinrich Degelo takes even more liberties regarding the standards of living with his artist and studio house in Erlenmatt, a district of Basel. A group of artists implemented the project as a cooperative. A foundation awarded the land and buildings to the cooperative as the property developer under hereditary lease law. In Switzerland, this is limited to 100 years. The artists consciously wanted to preempt the formation of property and thus remove housing from the market.

Artist studios, Erlenmatt Ost

Architect: Degelo Architekten

City: Erlenmatt, Basel, Switzerland

GFA: 2,600 sqm

Year: 2018-2019

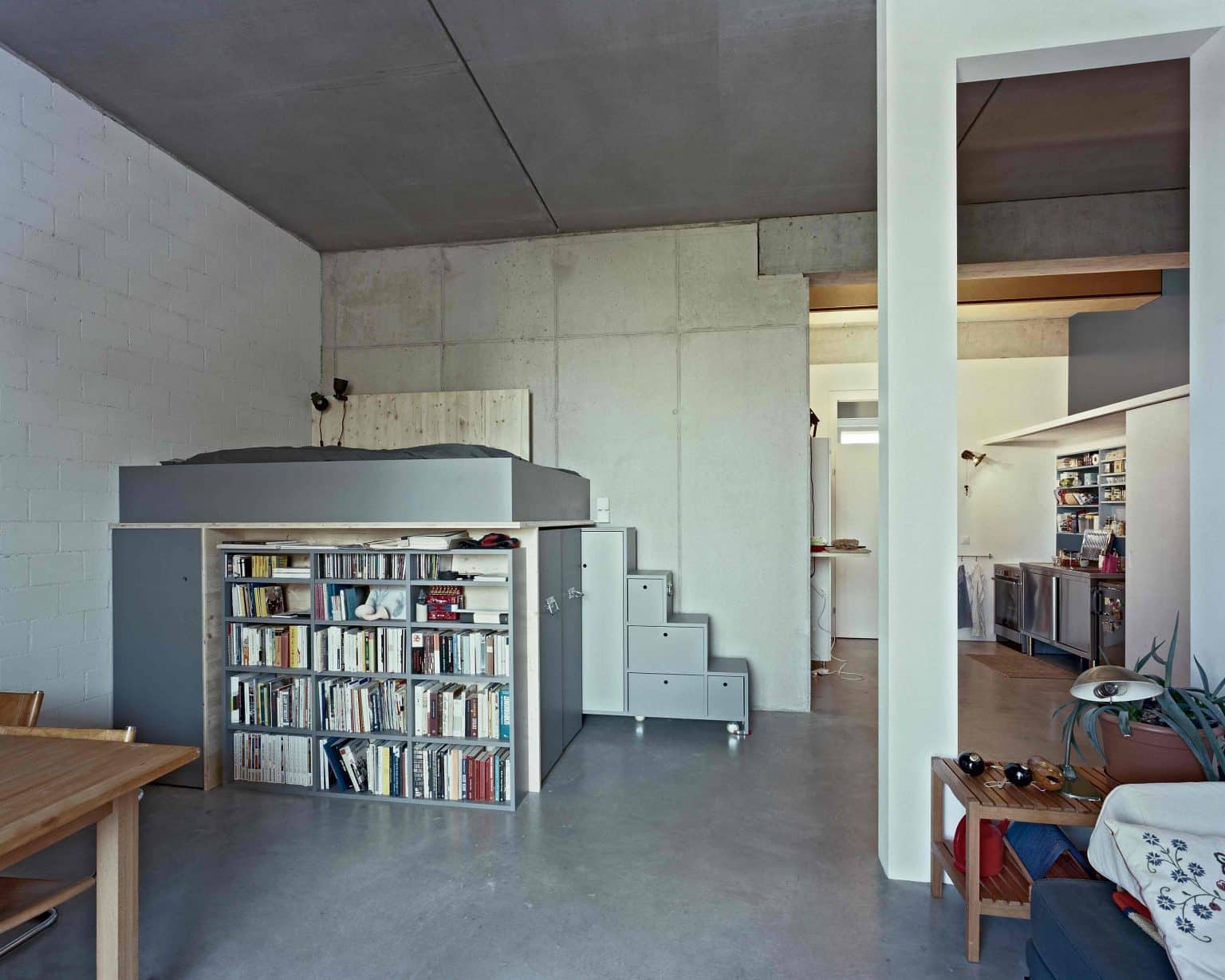

Sanitary element, artists and studio house Erlenmatt ©Degelo Architekten

The residents only encounter one sanitation unit in their apartments when moving in. “There is a shower, washbasin and toilet installed on the one side and then connections for kitchen units that are also included on the other side,” explains Degelo. The apartments do not include any interior walls as designed by the architects. The residents then decide themselves on the position and material of the walls. Almost all of them have installed the walls on their own.

The architect took a step back from his planning authority and is very satisfied.

“Following an initial phase of familiarization and furnishing, the cooperative members have now also become residents. It is fascinating how varied and imaginative the furnishing has become.”

Degelo Architects radically bid farewell to all residential standards and even do without heating. The heat in the apartments is generated only by the sun’s rays, as well as the residual heat from the refrigerator, lights or electrical appliances. Composite, porous bricks in the outer walls and triple-glazed windows keep the insulation level high. A sensor regulates the temperature in winter and summer between 22 – 25 degrees by opening the windows.

The artists live and work in the living and studio spaces, which average about 130 square meters. Some even live here with children. They enjoy the freedom of design, ecological construction and rents of CHF 10 per square meter. New buildings in the neighborhood charge CHF 30.

Light and ventilation against dreary apartment blocks

The Gap House by the South Korean architectural firm Archihood WXY is an example of how communal living concepts can be implemented even in an extremely dense urban environment. The Gap House is located in an area of Seoul that is very popular among students and young professionals. This has led to the construction of densely packed apartment blocks that are oriented on optimal use of space and profit. The anonymous apartment blocks offer no gardens or outdoor spaces. That makes them purely places to sleep that lack any residential quality.

Student housing, Gap House

Architect: Archihood WXY

City: Seongnam, Seoul, South Korea

GFA: 596 sqm

Year: 2014 – 2015

Archihood WXY are trying to break up the concept of dreary apartment blocks with dark access corridors.

Their building is grouped around a large courtyard that provides the apartments with additional light and ventilation. The atrium functions like a garden for the residents and offers a place to retreat to. Further common areas for kitchens, living rooms, toilets are provided across the floors. The balconies run like canals through the building, which explains the name Gap House. These outdoor areas, which are also used communally, offer the residents more privacy than unprotected balconies mounted on the façade. In contrast to its neighborhood, the building shows a great will of design. The block appears like a composition of four houses with highlights through the profiled gables on the corners. Inside there are unaltered materials such as wood on the floor or exposed concrete in the stairwells. These create a sense of atmosphere. The well thought-out building block design strengthens the identification of the residents with their living environment and thus also counteracts the anonymity of urban life.

The projects from Germany, Switzerland and South Korea are examples of housing forms that are a response to the new needs of building and living together. The architects meet the increasingly important ecological requirements for climate-friendly and resource-saving construction. Instead of profit expectations, they serve the increased demand for affordable housing.

Quality of life through community and neighborly relations are more important to these architects and residents than promises of luxury and loud wow-effects. Instead of repeating the same standards for floor plans and furnishing, the new residential types offer users flexibility and thus serve a completely different basic need: the need for freedom.