Stories

The Forgotten Temple

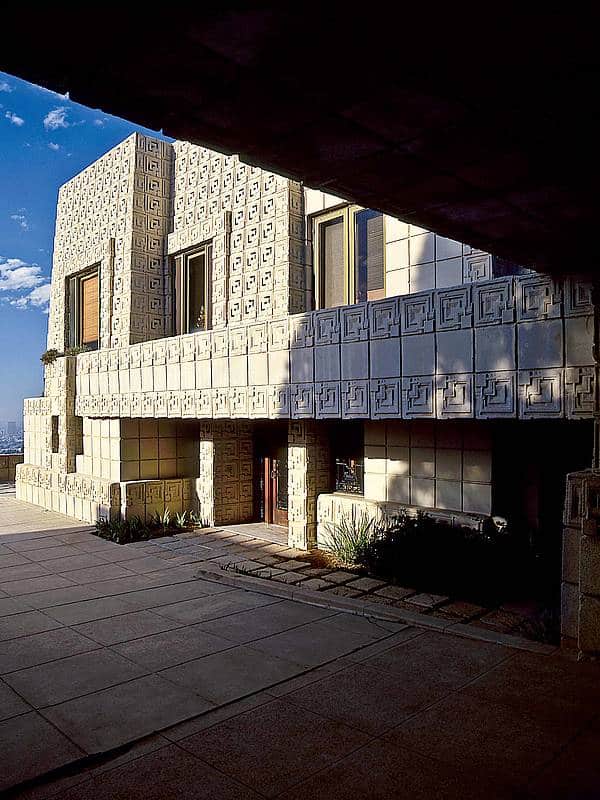

With his “textile block houses” in California, Frank Lloyd Wright wanted to establish rugged concrete as a decorative building material for all. His last design in this series, the Ennis House, is an architectural marvel – even though it lived a shadowy existence for years.

Only when an earthquake caused part of the facade to collapse did architecture enthusiasts remember the building in the hills above Los Angeles. Designed in the style of Mayan architecture and built from textured concrete blocks, the Ennis House expresses the vision of the great American architect Frank Lloyd Wright…establishing concrete as a multifaceted building material.

The building is the last of four designs that Wright had made from graphically arranged concrete blocks. He developed an individual design for each house. In 1932, the Millard House and the Storer House were built, with the Freeman House following in 1924. The Ennis residence became Wright’s favorite. The name “textile block houses” is due to the way in which the concrete blocks were connected to each other. A net made from steel bars that was threaded horizontally and vertically through the blocks was used to connect them and hold them in place.

Exclusively choosing concrete for the construction was revolutionary. The building material was a novelty. Typically, stone and wood were the construction materials of choice at the start of the twenties. Even Wright was inexperienced with this new material which was to become obvious after completion.

Inspired by Mayan culture

Wright saw several advantages in using concrete. It was a cheaper alternative to stone and was fire-proof, in contrast to wood. Concrete pressed into blocks was so easy to use that even laypersons could give it a whirl. The material could also be shaped, offering endless design opportunities. “Why isn’t it suitable for a new phase of our modern architecture? It might be permanent, noble, beautiful,” the architect later wrote. Wright was convinced that concrete was a building material of the future.

Wright received the commission for the Ennis House from menswear mogul Charles Ennis and his wife Mabel. As the pair were deeply interested in Mayan culture, he chose a meandering shape as the design on the concrete blocks for their house.

The imposing building on the hills in Los Feliz near Los Angeles is like a lost temple. The 6280 square feet are split up into three bedrooms, three and a half baths, a wonderful living and dining area, and staff rooms. The patterned concrete blocks decorate both the facade and the interior. They surround the fireplace in the dining area, accentuate individual walls and are stacked to create columns. The Ennis House is still the best modern interpretation of Mayan architecture to this day.

Hand-poured concrete blocks

The design of the “textile block houses” also shows Wright’s development as an architect. Before he arrived in Los Angeles in 1922, he mostly designed prairie houses in the mid-West. These properties were intended to give their residents shade and cool, but the overall effect was sometimes too dark. The four designs in Los Angeles, however, play with natural light. The atmosphere in the Ennis House changes with every hour that the sun passes by skylights and windows designed by Wright. One side of the house offers a view over the untouched hills of Griffith Park, while the other side observes the ever-changing Los Angeles.

Construction cost 300,000 dollars, a fortune at the beginning of the twenties. The concrete blocks made construction laborious and long-winded. Each individual block was created on site. Stones gathered on location were ground and mixed into the concrete to make it match the surrounding nature. The concrete was poured by hand into pre-made moulds, which created the graphic relief in the surface. Each block measured approximately 15-3/4 x 15-3/4 x 3-1/2 inches and had to dry for ten days before being used. Wright used between 27,000 and 40,000 blocks to create the Ennis House. While their design and construction were revolutionary, the textile block houses suffered from structural defects. The stone caused impurities in the concrete mix and impaired its weather-resistance. The perforated concrete, which was intended to let light through, proved to be leaky in strong rain. During rain, all four “textile block houses” had to be covered with tarpaulins.

Earthquake and rain damage

For his contemporaries, Wright’s designs were too far removed from the standard construction of the day. Frustrated, the architect left Los Angeles after two years and opened an office in Phoenix, Arizona. In the following years, the “textile block houses” were all but forgotten. Charles Ennis died four years after the building was completed. In 1940, radio presenter John Nesbitt bought the building and commissioned Wright with renovations. A pool was added on the north side, a staff room became a billiards room, and a heating system was added. In 1968, the eighth owner, Augustus Brown, tried to conserve the already weather-damaged concrete blocks by adding a protective layer. However, the applied film trapped water inside the blocks and the steel rods began to rust and discolor the concrete.

Although it was declared an architectural monument in 1971, people only began considering conserving the house in 1994 after the Northridge earthquake caused parts of the south wall to collapse. The Ennis Foundation, founded shortly after, took ten years to raise enough money for the repairs. In the meantime, record rainfall in 2004 heavily damaged the house again.

As the foundation could not cover the restoration costs of over 10 million dollars, it put the Ennis House up for sale in 2009 for 16.5 million dollars. Due to the property crisis, the house stayed on the market for two years. In 2011, the billionaire and philanthropist Ron Burkle bought the house for 4.5 million dollars and began restoration work, which is set to finish in 2017.

Photo: © Scot Zimmerman